Professional Practice

My professional practice project began in October while I sat waiting for a Preston-bound train at Liverpool Lime St. To kill time, I loaded some new film into the camera I'd been using - a Seagull, on my first outing with it - and looking down across the concourse to the opposite bench, I took the following shot:

It's an imperfect picture on almost every level: the focus is too soft, the original negative was incredibly underexposed, the image is still dirty (I'd neglected to clean it up), and the content of the photograph itself is entirely uninteresting. But after I'd put the camera back in my bag, I continued to watch this scene for another ten or fifteen minutes until I was able to board my train, and it occurred to me there that the only thing that we were all doing in this building was killing time. I'd loaded up a camera & watched the scene; the gentleman across from me had taken to eating his lunch; an elderly couple sat down and argued for a while. Some people were making transactions at Costa and Upper Crust, others were reading, staring at their phones, taking leaks, engaging in conversation. But essentially, we were all there to do nothing in anticipation for something to happen.

In this instance, the something was the arrival of a train, but something is variable: we wait for doctors, for phone calls, for the ATM, for news, for admission to gigs, movies, and sporting events, for taxis, and for service at shops and restaurants. The common denominator in these situations is the act of waiting.

Many people have photographed these acts of waiting, especially in its most universally recognized form: the queue. Steve McCurry even devoted an entire post on his blog to the concept of waiting, and the various forms that it can take, as illustrated by his own photographs and some overly-sentimental quotes.

|

Steve McCurry;

Crowds at the Kumbh Mela await their turn to bathe in the Ganges. Allahabad, India

|

Early contact with tutors in regards to this project lead me to questioning the direction that I should take with it. Martyn suggested looking into "queueing theory" - a mathematical analysis that seeks to determine (in a retail scenario) how many servers are needed to keep queue levels at a minimum while also being mindful of economic considerations. After searching through the Magnum online database, also at Martyn's suggestion, I'd concluded that photographs of queues were somehow too explicit and superficial for me. Similarly, Paul Hill's first reaction was a warning that I was at risk of taking photographs "of people just standing in line."

Rather than photograph people waiting then, I thought to remove people from the equation altogether and focus on the architecture of places where waiting primarily takes place, such as train stations and hospitals. Further discussion with Martyn prompted me to perhaps take it even further and consider why people are waiting (for traffic lights to change, to be served at the till, etc.) and photograph these objects and instances as well.

Though I haven't properly focused on architecture in the past, I have taken some photographs of architecture:

Eventually, this project evolved less into being less about places where people wait and more about the temporary places in which people just pass through. The places involved are more or less the same in either scenario, but the theory (of supermodernity and non-places; below) was a bit stronger, more layered, and inclusive of more places.

Theoretical Information

Psychology of Waiting / Delayed Gratification

My first instinct was to look at waiting from a psychological point of view, where it is directly related to self-regulation, an umbrella term defined as that which "encompasses a person's capacity to adapt to the self as necessary to meet demands of the environment". It covers patience, willpower, and self-control. Our tolerance for having to wait for something is also directly related to the level of "gratification" that we perceive to be at the end of it.

In 1970, American psychologist Walter Mischel conducted an experiment in which children were presented with a marshmallow and told that if they waited a little while before eating it, they would get a second one. Although it was a basic experiment, the results of which were dependent on each child's predisposition for self-regulation, in follow-up studies it was discovered that the children who were able to delay gratification carried that tendency into adulthood and generally achieved higher standardized test scores, had better social skills, were able to deal with stress more efficiently, and were less likely to abuse substances.

Although this information became somewhat irrelevant for my overall project, it still provides an interesting background.

Supermodernity, Non-Places, and Psychogeography

French anthropologist Marc Auge coined both supermodernity and non-places in his 1995 book Non-Places: Introduction to Supermodernity. The book itself is heavily-written - the vast majority of it concerned with defining and contrasting various anthropological ideas (seemingly unrelated and unnecessary to the casual reader but most likely included to somehow make the theory of the non-place more understandable in an advanced, ethnological sense) and other tangents, but the main theory itself is interesting and thought-provoking.

Auge starts by introducing the concept of supermodernity, which is defined by excess: of time (namely our perception of it, which according to Auge is affected by the present-day overabundance of information), of space ("shrinking of the planet"; ease of travel), and of so-called individualism ("do as others do to be yourself"). In short, supermodernity might be comparable to globalization and its effects.

In regards to non-places, which are symptomatic of supermodernity, he introduces them with this passage:

If a[n anthropological] place can be defined as a relational, historical and concerned with identity, then a space which cannot be defined as relational, or historical, or concerned with identity will be a non-place. The hypothesis advanced here is that supermodernity produces non-places [...] A world where people are born in the clinic and die in hospital, where transit points and temporary abodes are proliferating under luxurious or inhuman conditions (hotel chains and squats, holiday clubs and refugee camps, shanty-towns threatened with demolition or doomed to festering longevity); where a dense network of means of transport which are also inhabited spaces is developing; where the habitue of supermarkets, slot machines and credit cards communicates wordlessly, through gestures, with an abstract, unmediated commerce...

Basically, a non-place is that which we move through and which grants us a level of anonymity and solitude ("alone, but one of many"). Furthermore, they are spaces that, due to their universality, provide us with "relief" when we are in unfamiliar places (the example given in the book is a supermarket in an unfamiliar country. The supermarket is a non-place; the country as a whole, with its own historical relevance and identity, is a place). It's important to note that according to Auge, places and non-places aren't necessary separate or opposite from each other - there can be crossover, and any place essentially has the potential to become a non-place in future.

The primary spaces that Auge identifies as non-places - airports, train stations, supermarkets, banks, hotels, and motorways - were the same spaces that I identified early in this project as areas in which we are forced to wait around and areas that are temporary necessities (with the exception of his inclusion of the motorway, although traffic lights etc. were included in my initial list). Auge somewhat alludes to this too, saying that "since non-places are there to be passed through, they are measured in units of time."

Auge also briefly mentions the French philosopher Charles Baudelaire for a short comparison of modernity (Baudelaire is credited with having originally coined this term in 1864) and supermodernity, but he also mentions Baudelaire's tendency to travel aimlessly, which would also come to be a founding idea of the practice of psychogeography - urban wandering, the act of the flaneur.

According to writer Merlin Coverly, alongside this urban wandering, psychogeography also deals with "the imaginative reworking of the city, the otherworldly sense of a spirit of place, the unexpected insights and juxtapositions created by aimless drifting, [and] the new ways of experiencing familiar surroundings."

Psychogeography takes form in literature, the arts, etc. An example of it in photography can be seen in Stewart Home's How I Discovered America (2002), in which he argued that America "exists everywhere as a state of mind" (source) and then photographed areas of Britain in an attempt to find it:

|

| From How I Discovered America (2002) |

Together, these theories helped found the basis of my project. Mostly taken from Auge's theory on supermodernity and non-places, I'm focusing on the architecture and character of the spaces that he considers non-places.

Photographic Influences

Roughly organized chronologically.

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946) & Alexander Rodchenko (1891-1956)

Moholy-Nagy was a multi-disciplinary Hungarian artist involved with the Bauhaus (1919-33) in Germany from 1923.

| Untitled painting (1927) |

Rodchenko was a Russian artist involved with Constructivism who also worked with photography.

|

| Stairway (1930) |

|

Superstructural Abstraction (1928) |

|

| Compass and Ruler Drawing 2 (1914-5) |

Rodchenko and Moholy-Nagy both utilized unusual points of view in their photography and the city was often their subject, both of which were typical of the time. Although I'm interested in more objective points of view (below), I nevertheless enjoy the use of lines and shapes inherent in this photography, but also in their paintings as well.

Karl-Hugo Schmolz (1917-86)

Schmolz' was a German photographer who worked with an objective viewpoint that would eventually come to be implemented by Bernd and Hilla Becher and the American photographers involved with New Topographics. Where New Topographics stepped back however, Schmolz still seemed to prefer to fill his frame with architectural detail.

|

| Tankstelle Ecke (Gas Station Corner) Oskar-Jäger-Straße (1952) |

|

| Architectural images of buildings in Cologne, c. 1950 |

New Topographics (c. 1975)

New Topographics is an American photography movement that takes its name from a 1975 exhibition at the International Museum of Photography: New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape. Artists included were Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Frank Gohlke, Stephen Shore, and the Germans Bernd and Hilla Bechner. Overall, the landscapes offer a banal and deadpan aesthetic, and they are centred around human presence on the land.

Topography, as a standalone concept, is defined as "the arrangement of the natural and artificial physical features of an area" and usually involves mapping and the surveying of the land. Together, these photographs illustrated the urban and suburban sprawl of the 1970s, particularly into areas of the American West, and they were a departure from the visually-immense landscapes by the likes of Ansel Adams.

Many photographers in the exhibition shot on large format. The titles of individual photographs are purely descriptive: street addresses, cities/states, and dates.

|

| Robert Adams, Mobile Homes, Jefferson County, Colorado (1973) |

|

| Frank Gohlke, Grain Elevator, Dumas, Texas (1973) |

|

| Lewis Baltz, Foundation Construction, Many Warehouses, 2891 Kelvin, Irvine (1974) |

|

| Lewis Baltz, South Corner, Riccar America Company, 3184 Pullman, Costa Mesa (1974) |

Although New Topographics is immediately associated with black and white photography, Stephen Shore - a pioneer for colour photography - exhibited work in colour.

|

| Stephen Shore, U.S. 1, Arundel, Maine, July 17, 1974 |

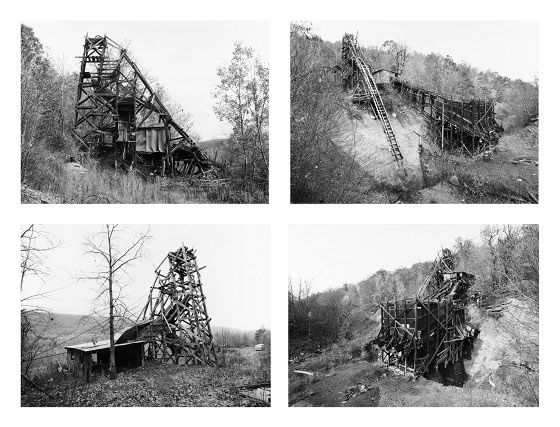

The inclusion of Bernd and Hilla Bechner, known for their purely objective photographs of industrial structures, is apparently suggestive that the overall New Topographic aesthetic has something "decidedly European" about it. (source)

|

| Bernd and Hilla Bechner, Pit Head, Bear Valley, Pennsylvania (1974) |

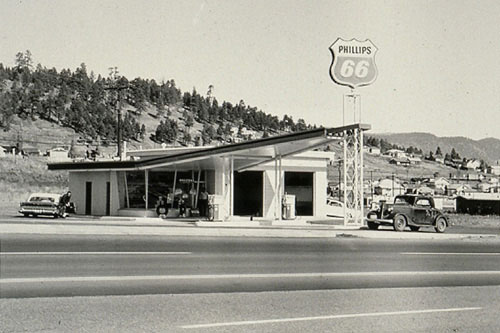

It's also important to note that New Topographics is frequently read as being influenced by the works of Robert Frank (The Americans, 1958), Jack Kerouac (particularly On the Road, 1957), and Ed Ruscha (Twentysix Gasoline Stations, 1962).

|

| Ed Ruscha, from Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1962) |

Mark Power (b. 1959)

Power is a British photographer whose aesthetic is similar to that of the New Topographic photographers of the 60s, but it's also conceptual. For example, his project 26 Different Endings (2003-6) is an example of psychogeography, in which he took the A-Z London Street Atlas, the outer parameters of which are apparently redefined every year, and photographed the "unfortunate places that fall just off the edge" of the border between what is considered to be London and what isn't.

|

| B 111 East from 26 Different Endings |

|

| C 131 South from 26 Different Endings |

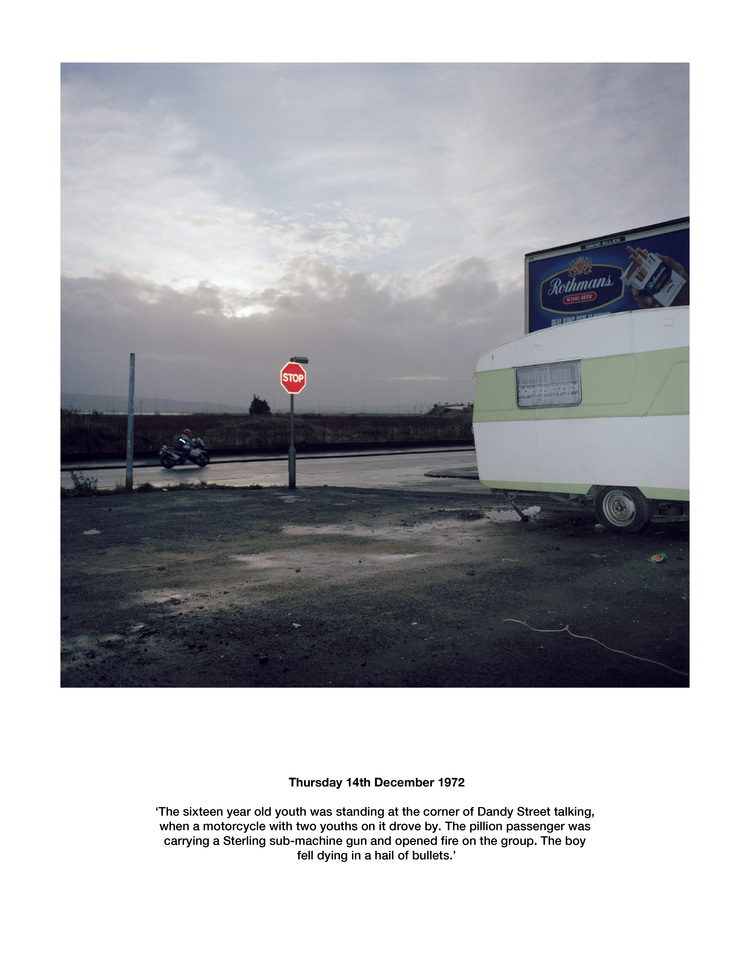

Paul Seawright (b. 1965)

Like Mark Power, Seawright's landscapes are also bound to broader concepts. His series Sectarian Murder, presented alongside newspaper clippings, revisits specific places where people were murdered for their religious affiliation during the unrest in 1970s Northern Ireland. In the Missing, he looks at the landscape of "the peripheral world where those who are missing from society exist" (source).

I'm really interested in working with photography this way, where the meaning of the images is more implicit and understated, but nevertheless tied to something significant or thought-provoking.

|

| From Sectarian Murder (1988) |

|

| From the Missing (Date unknown) |

Martin Cregg (b. 1976)

Martin Cregg is an Irish photographer and educator based in Dublin. Though obviously deriving influence from the New Topographic movement, Cregg seems more interested lines and forms, as seen in the likes of Schmolz & Moholy-Nagy. In A Suspended State, he looks at the industrial areas that were abandoned following Ireland's economic collapse in 2008.

Cregg shoots with a Mamiya 7 and a Mamiya RB67.

|

%20WORKED%20on.jpg) |

| From A Suspended State |

Another photographer also refers to the "Celtic Tiger" (Ireland's period of economic growth from the mid-90s to 2008) narrative in his work. Entering homes and offices spaces that were built during the economic boom but never occupied due to the recession, Johnny Savage offers a different photographic representation of the same story:

|

| Johnny Savage, from the 2014 series Fallout |

In A Fading Landscape, Cregg also makes use of a lot of blank space, which I find visually appealing and suggestive.

|

|

| From A Fading Landscape |

Mattias Heiderich (b. 1982/3)

Heiderich is a German photographer who literally meanders around cities and photographs architectural forms. Although his work is void of any significant contextual background, I find his photography incredibly visually appealing. He shoots both on medium format and digitally.

|

| From Stadt der Zukunft |

|

| From Northbound |

|

| From Color Berlin |

Ignacio Acosta (b. 1976)

Acosta is a London-based Chilean artist who I had the opportunity to work with on a more theoretical level in May 2015 during his residency with the Liverpool International Photography Festival (LOOK/15). My primary job was to provide public updates on his residency and promote his previous work on the LOOK/15 blog ahead of talks and events that he was hosting during the festival. Although I didn't work with him photographically, the experience gave me some insight into how he created these photographs, and perhaps more importantly, it gave me tangible, first-person insight into how geography, history, and economic issues (or, more broadly speaking, non-photographic subjects) can be investigated through photography.

Acosta's Copper Geographies (and the sub-projects that constitute it) primarily surrounds minerals, their economic power, and the geographic relationship between where they are mined and where they are refined and distributed. He shoots on large format.

|

|

| From Copper Geographies (2010-15) |

|

| From Miss Chuquicamata, the Slag (2012) |

Naoya Hatakeyama (b. 1958)

Hatakeyama is a Japanese photographer primarily known for his large format photographs of exploding limestone quarries.

His project Tracing Lines / Yamate-Dori appeared in the Summer 15 issue of Aperture magazine. Here, he focused on parts of a 10km stretch of Tokyo highway that had been closed for construction. Rather than taking expansive photographs of the highway, in use or otherwise, Hatakeyama focuses on corners and "claustrophobic" spaces along the road instead.

Because the highway is closed, there are no people that appear in these photographs, which was largely influential when I was determining the direction of my own project. Japan Times says:

In past interviews, he has referred to photography as a medium that can trace lines that he sees as metaphors for the relationship between humans, nature and the city. Perhaps this is why we rarely see people in this series of photographs; instead their existence and effect on civilization are signified by the synthetic structures and saturated colors of their creations.

|

| From Tracing Lines / Yamate-Dori (2008) |

Kris Moore (b. 1995)

Moore is a young photographer based in Manchester, and I found the following work on the contemporary photography blog iGNANT. Titled Kanojo (Japanese for her), Moore uses the anonymous model in these images in order to "highlight our relationship to objects and places around us."

In this work, I really enjoy his use of space, so much so that the model almost becomes incidental, but I can also appreciate his reasoning behind using a person in order to exemplify space as I have also attempted the same in some of my past work:

|

| My work; 2014. |

Andy Feltham

Feltham works as a medical professional in Northampton. His work is "born from [his] desire to re-examine the commonplace; to confront and question the monotonous. [It] aims to celebrate the incongruous marriage of perceived isolation with an overriding sense of wonderment."

I haven't taken too much from this work, but I enjoyed the curious nature of his images.

|

| A45 from Incidental View |

|

| Racecourse 4 from Incidental View |

Dissertation Relevance

Although my dissertation on Japanese photography and my professional practice don't directly correlate (other than perhaps citing Naoya Hatakeyama as one of my influences here), I feel that the information gained through my dissertation study allowed me to appropriately research relevant movements for my PP. I understand that architectural photography has a long tradition in German photography, from Mattias Heiderich back to Moholy-Nagy - himself Hungarian, but an important figure within the Bauhaus, which is arguably where the German interest in architectural photography traces back to. So, even though my PP has little relation with Japanese photography beyond Hatakeyama, my dissertation was useful in helping me properly understand various photographic movements in various countries.

Also, despite taking most of my photographic influence for this project from German or otherwise European photographers, I've long been interested in Japan's vast urbanization, particularly of Greater Tokyo, which consists of multiple cities. With 93% of Japan's population living in an urban area as of 2014 (source), much Japanese photography revolves around the city (typically Tokyo or Osaka):

|

| Takashi Homma, from Tokyo and My Daughter (2002) |

|

| Eiki Mori, from tokyo boy alone (2006-11) |

Workflow

Early work

Originally, I was intending on making use of medium format photography in order to both achieve a square image format and satisfy the brief's condition of using foreign-to-us technology. These are two early images from this project, shot using a Seagull TLR and HP5 film:

This early period was very stop & go for me, and eventually I was persuaded to revert back to digital. The below images were test shots taken on a Sony Nex-7, but with very little technological consideration (ie; I used a large aperture to achieve appropriate exposure, rather than use a small aperture to increase the depth of field and a tripod to slow the shutter speed down.) The locations also had little to do with my wider concept:

Nikon D700 & Nikkor 45mm f/2.8 PC-E

After the test shots on the Sony, I took out a full-frame Nikon and a PC lens.

The majority of the photographers that I looked at during this project shoot on 5x4 or 10x8 large format cameras, and initially, I assumed that this was due only to the sharpness of large format photography. While this is an undeniable feature of large format, the cameras also have innate tilt shift capabilities, which are incredibly useful in maintaining perspective control.

In digital photography, this is achieved by using a tilt shift/perspective control lens. These lenses are available in various focal lengths. By keeping the camera body level and shifting the lens itself, perspective is maintained. Tilt shift lenses can also be used for selective depth of field.

Perspective can also be corrected in post-processing, albeit with some damage to the image (evident with large-scale printing.)

These are a few of the first images taken in Manchester, using a 45mm Nikkor tilt shift lens on a full frame D700:

I soon found that the PC lens, while great to use, was also quite hard work. The tripod of course slowed me down - not necessarily a bad thing as it forced me to be more thoughtful about the photographs that I was taking. However, the tripod was also considered by some to be a "security risk" and I wasn't allowed to use it in some of the locations that I had selected. In the end, I would revert back to using my mirrorless Sony, which was much more inconspicuous than the full frame Nikon atop a tripod. However, using the Nikon and the PC lens was beneficial to me all the same as I was careful to shoot level with the Sony to try and maintain perspective.

Sony NEX-7 & Sigma 30mm f/2.8

Combining the 30mm lens with my Sony's crop sensor gave the images roughly the same focal length as the 45mm PC lens on the full-frame D700.

Annoyingly, the NEX-7 only offers two aspect ratios - 3:2 and 16:9 - but its live-view screen is incredibly efficient compared to that of a DSLR, so I made a 1:1 mask with black window film over the screen and shot through that, leaving my viewfinder available for shooting 3:2.

These were a few of the first handheld photos that I took, hand-held, with the Sony:

As I stated above, shooting with the Sony felt much more natural to me and was a more enjoyable experience. It also allowed me to approach shooting in a more flaneuristic sort of way - just wandering around the city and stumbling upon locations that I hadn't previously known about.

Spaces vs. Buildings

After I'd shot the above images (and others), Paul Hill advised me during a tutorial to keep an eye on my consistency, and that my strongest images (in relation to my concept) were the ones that were of spaces. At this time, I was indeed starting to stray off into abstraction and although I already perceived that these images weren't quite as strong, it was Paul's advice that really rationalized it for me. The following images are of buildings rather than "spaces", which I then realized are areas that can be (regularly) occupied by people (typically ground-level). The following photos aren't "spaces":

Richard had a different take on this, remarking that sometimes it was work having these sorts of images to break things up.

Final Selection (as of January 2016)

Although I haven't yet finished shooting for this project, this is my final selection:

Some images were removed due to soft focus on the prints, or else because I simply felt they weren't strong enough. I've also opted to take Richard's advice on the buildings that aren't really "spaces" for now; if I determine that the series works better without them at its completion, they'll be removed.

In the end, I aim to have 25-30 strong images by the end of Professional Study. In particular, I need to start focusing more on train/bus stations, roads, and shopping centres. The majority of these images are of hotels, hospitals, and car parks.

No comments:

Post a Comment